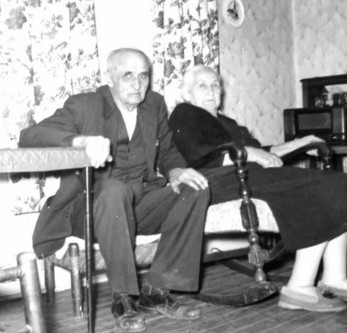

Harry & Pauline

HARRY and PAULINE

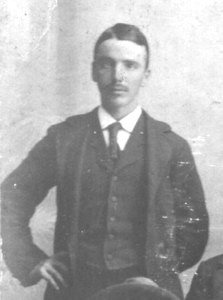

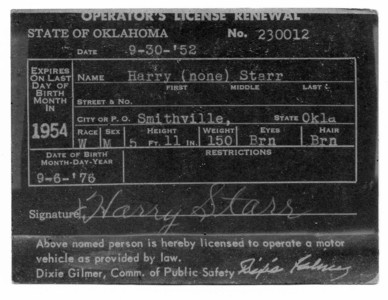

Harry Starr (1876-1954)

and Pauline Olivia Rankin (1877-1966)

Copyright July 2012 by Linda Sparks Starr

Harry and Pauline look somberly at the camera in this picture taken in the early 1950's in Kansas City. People born

in the Victorian era rarely smiled for photographs, they thought smiles would make them look foolish or unserious.

Although both grew up in middle class Georgia households, the early

years for Harry and Pauline couldn’t have been more diverse if

one designed them to be. Harry, reared by a single father, grew up in a

small rural Georgia community south of Atlanta. His father was a

medical doctor, but they likely lived on the profits from the small

general merchandise store he operated on the side. Understandably,

between two careers, Dr. John had little time for his growing son.

Harry’s Aunt Mary (Griffin) Tucker and her husband Thomas

welcomed Harry into their home at all hours of the day and night.

Although both grew up in middle class Georgia households, the early

years for Harry and Pauline couldn’t have been more diverse if

one designed them to be. Harry, reared by a single father, grew up in a

small rural Georgia community south of Atlanta. His father was a

medical doctor, but they likely lived on the profits from the small

general merchandise store he operated on the side. Understandably,

between two careers, Dr. John had little time for his growing son.

Harry’s Aunt Mary (Griffin) Tucker and her husband Thomas

welcomed Harry into their home at all hours of the day and night.

Harry

had fond memories of this extended family consisting of three children.

The oldest were twins Monnie and Marcia (names as they appear on the

back of

their photo); a boy, Dolphus, was born the same day Harry’s

parents were

married.

>>>>

Harry was nine years old when Dr. John married

the sixteen year old Katie Orr. Understandably the relationship

between Katie and Harry was strained from the very beginning. Harry had

an aptitude for math and one of the best math teachers in the

state taught in Calhoun, Georgia. Besides the opportunity for future

advancement for Harry, this also eased the tension in Dr.

John’s household. Until this time Harry’s known world

consisted of Sunnyside, possible trips to nearby Griffin, and visits to

his relatives living only a few miles away. No one dreamed the train to

Calhoun was also taking him to meet his future wife, Pauline Rankin.

The bustling city of Calhoun was a far cry from little Sunnyside.

Located on the direct railroad route between Atlanta and Chattanooga,

it was competing successfully with other communities for new industries

along that corridor. Pauline’s father purchased the nearest

boarding house/hotel to the train depot, giving Pauline opportunity to

meet travelers from all over. The trains took members of the

Rankin family back to South Carolina for semi-regular visits with

relatives. Thus during her early years Pauline was exposed to a far

wider world than was Harry. Moreover, Pauline’s father was a

well-known and respected local and state politician and had diverse

business interests. Little happened that escaped discussion

around their dinner table.

The bustling city of Calhoun was a far cry from little Sunnyside.

Located on the direct railroad route between Atlanta and Chattanooga,

it was competing successfully with other communities for new industries

along that corridor. Pauline’s father purchased the nearest

boarding house/hotel to the train depot, giving Pauline opportunity to

meet travelers from all over. The trains took members of the

Rankin family back to South Carolina for semi-regular visits with

relatives. Thus during her early years Pauline was exposed to a far

wider world than was Harry. Moreover, Pauline’s father was a

well-known and respected local and state politician and had diverse

business interests. Little happened that escaped discussion

around their dinner table.

Pauline was one of seven children. All received the best

education their father

could afford. The girls were brought up to be

“southern ladies.” This encompassed the arts of playing

a musical instrument, singing, giving recitations and conversing

with gentlemen. There would be others to do the drudgery of house

cleaning and laundry.

Pauline was one of seven children. All received the best

education their father

could afford. The girls were brought up to be

“southern ladies.” This encompassed the arts of playing

a musical instrument, singing, giving recitations and conversing

with gentlemen. There would be others to do the drudgery of house

cleaning and laundry.

Although she attended private academies from time

to time, Pauline graduated from Calhoun High School. The list of honor

students for 1889 includes Pauline, her brother George, and friends

Eva, Cornelia and Dora Cantrell.

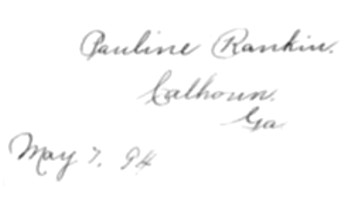

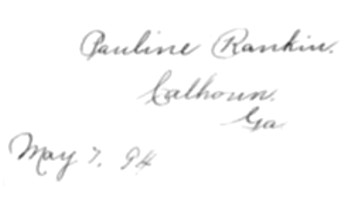

An example of her penmanship shows her fine, precise hand. The photo was taken in the 1880s.

Copies of pages in the family bible that documented Harry and Pauline's marriage and the births of the children may be seen here.

From here on, Harry and Pauline’s story is told by use of

extractions from Harry’s pension application and interviews over

the course of several years with three of their children, a son-in-law

and narratives written by two grandsons and one granddaughter. The key to narrator:

ALICE (Starr) Schisler

GLADYS (Starr) Campbell

JACK – Jack Starr

JS – (son-in-law) Jack Schisler

JERRY – Gerald “Jerry” Starr, son

of Jack

DAVID – David Starr, son of Jack –

from English assignment dated 1955.

JEAN – (Starr) Whipple, September 2000,

daughter of Jack

Readers may note some minor discrepancies between the various accounts.

Some factual errors may be observed (e.g., that Harry "went around the

world" while in the military is an exaggeration--he traveled from New

York to the Phillipines).

That is to be expected in memories stretching back many decades. Here

there has been no attempt to fact-check their stories, but rather to

let them speak in their own words.

JACK: Harry, born 6 September 1876 in Sunnyside, Georgia, was the

only child of Dr. John Pinkston Starr and his first wife. Harry

was only eighteen months old when his mother died; he was “mostly

raised” by his maternal aunt. Harry and his cousin [Dolphus

Griffin; see picture above] got into the usual boy-mischief troubles together.

One

of their more serious offenses was swiping chloroform from Dr.

John’s medicine bag. They enticed another boy to sniff this

substance which rendered him unconscious. Even though the boy

recovered, they regretted this prank later when they understood the

possible consequences. Harry was nine years old when his father

married a sixteen-year old. Perhaps the closeness of their ages is one

of the reasons they never really got along. Harry received his

elementary education in Sunnyside. He showed a great aptitude for

mathematics so was sent to a school in Calhoun known for its excellent

math teacher. This teacher prepared Harry for jobs he held

throughout his adult life. It was while attending this school in

Calhoun that he met Pauline.

After graduating from the school in Calhoun, Harry went to Dallas,

Texas and worked in a dairy for some time. The Spanish-American War

started while he was in Dallas and he enlisted in the Army and served

in the Hospital Corps. He was first sent to Brooklyn, New

York to serve for six months in the Navy yard. It was while he was

in Brooklyn that his great love of the game of baseball grew. His ship

went to Havana, Cuba, and eventually circled the world. The Corps

went to the Philippines to get some critically ill soldiers to take to

San Francisco. His last assignment was to accompany a terminally ill

soldier back to Alabama. The soldier’s parents were waiting at

the railroad station to receive their son. Harry said one of the

saddest things he ever had to do was help lift this soldier and lay him

in the back of his parent’s wagon. He never saw the soldier

again. In later years Harry stated he was perhaps the only

soldier of the U.S. Volunteers to serve in both Cuba and the

Philippines without re-enlistment. Some souvenir pictures from his time in Cuba can be seen here.

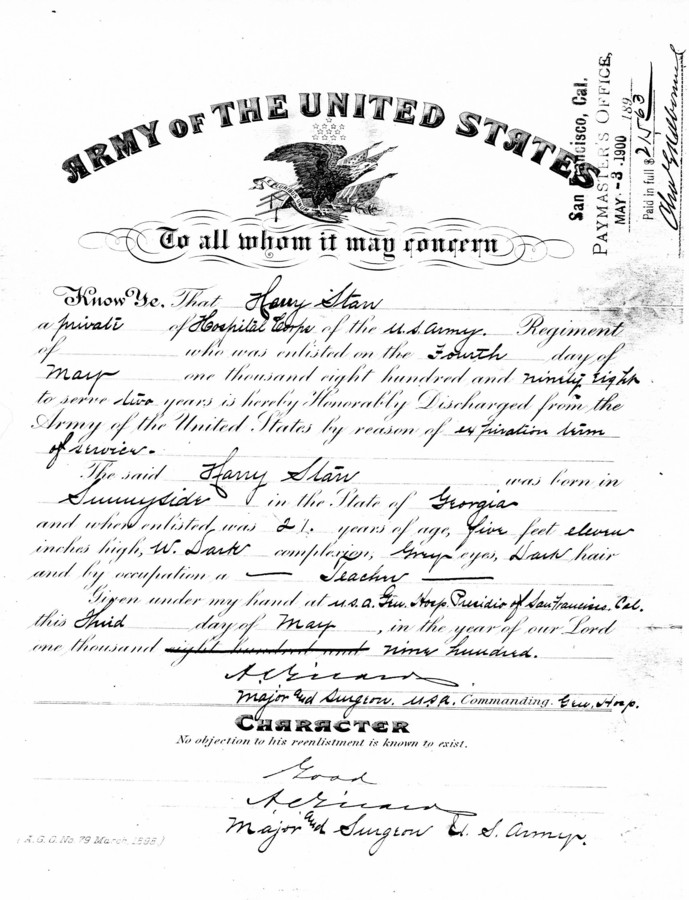

HARRY (age 47 supplemental affidavit for Pension dated 23 October 1923):

“I enlisted at Austin Texas

on May 4th, 1898 in Co K of the

2nd Texas Vol. Inf. We

were moved from there to Mobile Alabama thence

to Miami Fla. There in the month of July I was transferred to the

Hospital Corps. We were moved to Jacksonville Fla. and thence to

Savannah Ga. Here I was detached with two others for service in

Hospital Corps with Signal Corps. In December 1898 we were taken to

Havana Cuba and remained there until about May 1st, 1899. Then I was

transferred at my own request to the Hospital Ship Missouri. [Note: The

Missouri (the subject of the painting at right), one of America's

earliest hospital vessels, saw heroic service even before the war with

Spain. For an interesting account, go to

this

site. The

Missouri's

dramatic rescue in 1889 (before it became an American vessel) of the singking

Danmark's passengers is

depicted

here.] After

making a trip to Newport News, we went to Brooklyn N.Y. for repairs and

on Oct 16, 1899 we started to Manila P. I. and landed there about Dec

1st 1899. We left Manila P.I. about Jan 1st, 1900, and arrived in

San Francisco Calif in Feb 1900 where I remained on Duty until I was

discharged on May 4th 1900. I was given an honorable discharge by Major

A. C. Gerrard.” [file #1,490,903 Veterans

Administration]

Harry at camp in Florida >>>>>

The Early Years Together

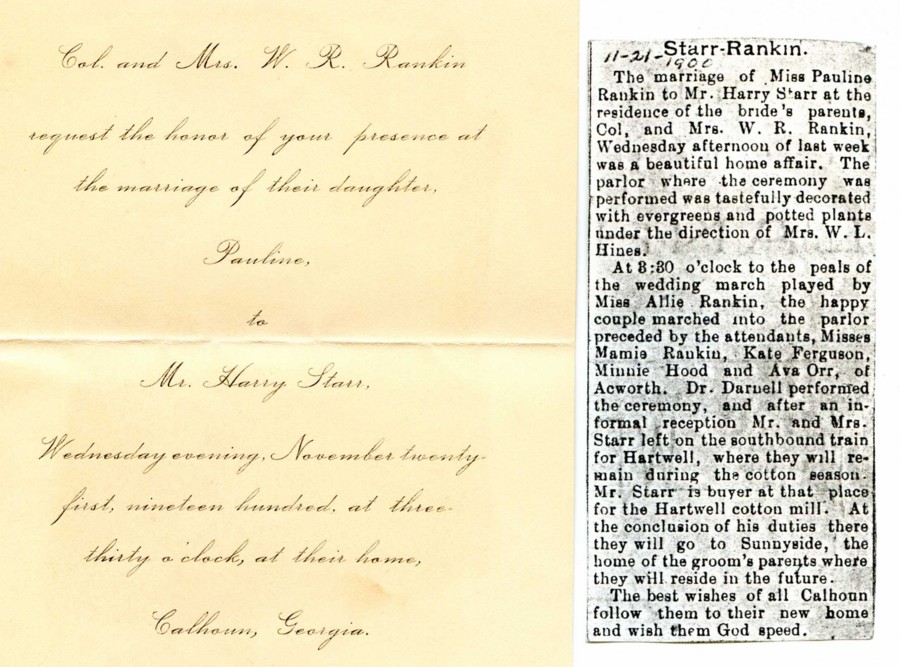

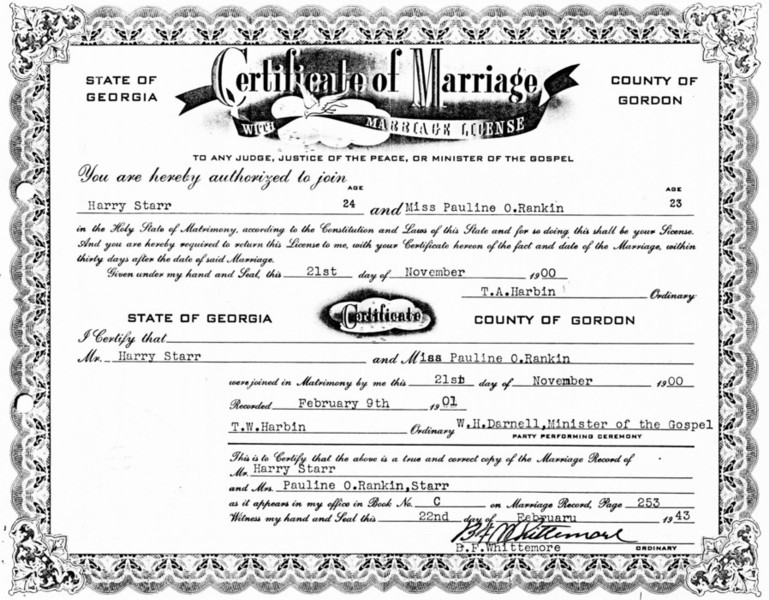

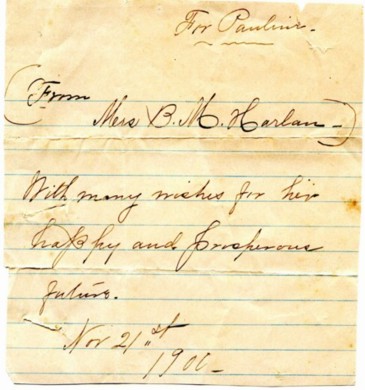

JACK: After his discharge and return to Georgia, Harry continued on to

Calhoun where he and Pauline were married. They had dated

for a long time, but had never set a date for their marriage.

According to Papa who “loved to tease and joke and told this with

a mischievous grin,” when he returned after his service, she told

him they either set the date or forget about it. They were married

Wednesday evening, November 21 at 3:30 p.m. in her parent’s

home by a Presbyterian minister. She was twenty-three and Harry

twenty-four.

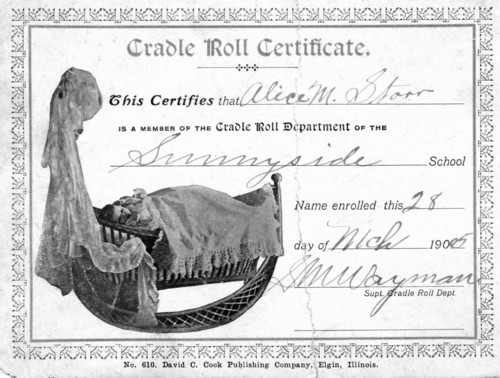

Their first home was in Sunnyside where Harry managed his

father’s grocery store for the next few years. They lived in a

house not far from his father and step-mother. Four children were born

here, all delivered by their grandfather, Dr. John P. Starr. All were

baptized in the same church Harry had been baptized in. It was also the

same church where Dr. John had married Harry’s mother; but, it

was called Shiloh Methodist then. Their relationship with step-mother

Kate was not a good one and they wanted a different life.

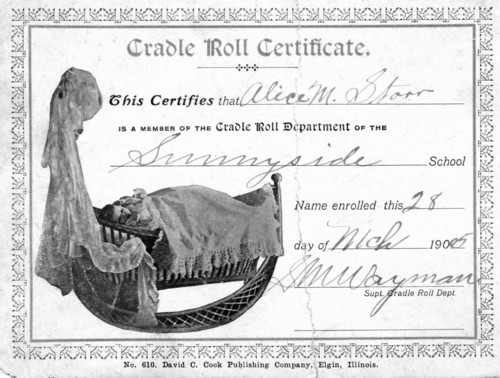

Baby Alice

The house where Alice--and presumably William, Harry and Estelle--were born.

ALICE: Papa and my Grandpa had a store in Sunnyside and

they decided they didn’t want to run the store together

anymore. Papa wanted to make a change and they moved up to

Calhoun. Uncle King

[Norton] was a salesman; they were called a drummer

at that time. He had a good job and he wanted Papa to do that

too. He got Papa a job, but Papa had to be gone from home so much. Mama

had four little children – I was only four and a-half -- so

she said he ought to be home to help her instead. Uncle George

[Rankin] – Mama’s brother – wanted Papa to come

West.

At that time people were coming West to seek their fortune. It seemed

everybody who came West got rich. Some people made money on cattle and

lumber. Papa decided to come West to get his fortune and we came.

JACK: Pauline’s brother, George, had moved to Arkansas

earlier and it was decided to join him. They traveled by train to

Arkansas, but Harry always said he walked the entire way. Their

youngest child, Pauline Estelle, was ill when they left Georgia and

Harry carried her in his arms while walking back and forth the length

of the train.

Pauline Estelle

Estelle next to Margaret (Ramsay) Rankin

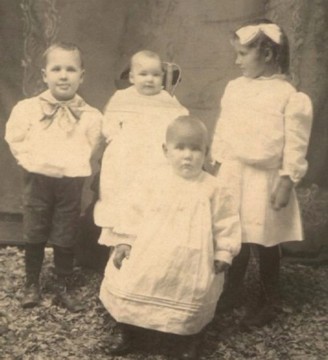

1906:

William, Estelle, Harry, Alice

ALICE: We left Calhoun, the first time, in the spring of 1906. We came

to Arkansas first, lived at Cove a little while. We lost our little

sister to an infected spider bite when we first moved to a saw mill

set. [Pauline Estelle Starr died 20 September 1906

near Cove, Arkansas, 11 months, 9 days old. Buried in unmarked

grave in Cove Cemetery.]

JACK: They moved from Cove into Oklahoma which was then Indian

Territory. ALICE: They sent him out to the

sawmill – sets they called them. We lived in several places

because they had to move the sets to where the timber was.

Papa had charge of hauling logs. He drove teams of mules and some

oxen. He had helpers. He used oxen because they could get through

the mud better than horses. DAVID: He did logging and sawmill

work where they were paid by a grocery order, beans and salt-pork with

a little flour, those being the staples for each week.

HARRY: (Letter to Helen dated November 20th, 1929 – ink

blotched): “Twenty years ago this date I was driving four

oxen and hauling a load of ____ver, that is not the only thing that

happened that day. We were all petting and smiling at a little baby

girl that we decided was as pretty as Helen of Troy. ... We are still

just doing ... as well as usual ... We are raising two or three

chickens for the time [you will come home] and it will be the old tune

of ‘kill a chicken and churn.’ ...

GLADYS: During her childhood and while living in Sunnyside after

her marriage, a black laundress took care of all the laundry chores for

Pauline’s family. Until the move west, she had given little

thought as to what was involved. Once they moved, it was necessary she

do it all. She observed that a huge pot was filled with water and then

a wood fire was built around it. Finally, one combined hot water

and soap, then scrubbed the clothes in the pot on a scrub board.

So she set herself to the task. During that first attempt, she was

horrified at the sight of a grayish scum forming in the water as it

heated. She tried skimming, but more scum formed. She just

sat down and cried. Another lady in the camp saw her crying and

came over. The lady  was amazed that Pauline did not know to

“break” the water by adding a little lye. Pauline was

even more amazed when the lady offered to do the laundry for her. This

gesture shocked her. She had never heard of white folks hiring out to

do laundry. But she was delighted and Pauline became the first woman in

the camp to hire a laundress. I heard Mom tell this story many

times.

was amazed that Pauline did not know to

“break” the water by adding a little lye. Pauline was

even more amazed when the lady offered to do the laundry for her. This

gesture shocked her. She had never heard of white folks hiring out to

do laundry. But she was delighted and Pauline became the first woman in

the camp to hire a laundress. I heard Mom tell this story many

times.

The logging camps were located in densely wooded areas and there were

many wild animals – deer, bobcat, snakes, panthers, etc. –

around. On the first night after one of these moves, they had

gone to bed and the only noises were those of owls and distant night

birds. The baby (Helen, then about one year old) slept between my

parents. During the night my father awakened; his hand was

grasping a smooth, sleek, round object. He was almost petrified with

fear, but managed to awaken my mother and told her to gently get out of

bed and take the baby – that there was a snake in the bed with

them! Her exit was one of haste, as she quickly grabbed the

baby. Poor Helen: her arm was almost torn from the socket

for my father’s grasp around “the snake” was quite

firm.

JACK: Life was very hard and Pauline longed to return to Georgia.

Her father sent money for her and the children to come home for a

visit. Before she left, she and Harry decided to return to Georgia; he

promised to follow as soon as he could.

ALICE:

Mama, William, Harry [Jr.] and I went back to Calhoun and stayed five

months. Papa had the stock and he couldn’t get the price he

wanted. Things got a little better and we came

back.

Helen as a

baby..

JACK: Papa never managed to accumulate enough money to move back

to Georgia and was too proud to ask either parent for help. Besides, he

liked Oklahoma and really didn’t want to return to Georgia.

Pauline was unhappy being away from him and after several months, she

asked her father for the money for the return trip to Oklahoma. She

returned to Georgia only twice more during her life and those trips

were made many years later.

JACK: Papa never managed to accumulate enough money to move back

to Georgia and was too proud to ask either parent for help. Besides, he

liked Oklahoma and really didn’t want to return to Georgia.

Pauline was unhappy being away from him and after several months, she

asked her father for the money for the return trip to Oklahoma. She

returned to Georgia only twice more during her life and those trips

were made many years later.

Cup given to Alice by her grandfather, W.R. Rankin, just before she

left to return to Oklahoma. >>

JERRY: Were the Rankins unhappy about the move out to

Oklahoma? ALICE: Unhappy! They thought we were

going out of the world, that is was wild and woolly out here. When we

left, the Snake [Shoshone] Indians were fighting among themselves and

Mama was scared to death. She kept William, Harry and me right around

her all the time. One day Papa told Simon Bear, one of the

Indians, that “my wife’s afraid of Indians.” Oh

says he: “We’re not going to hurt you white

people.”

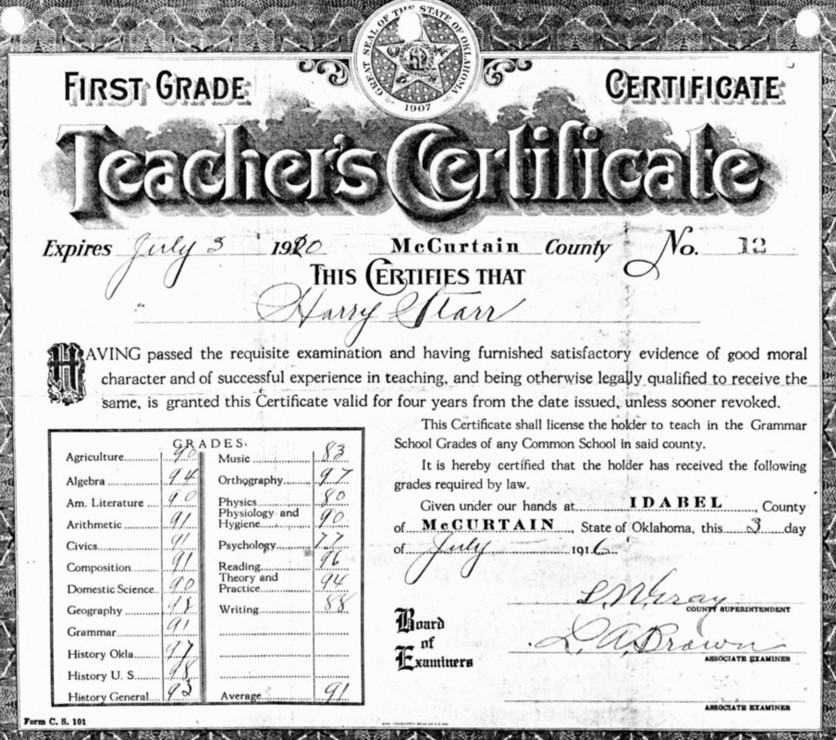

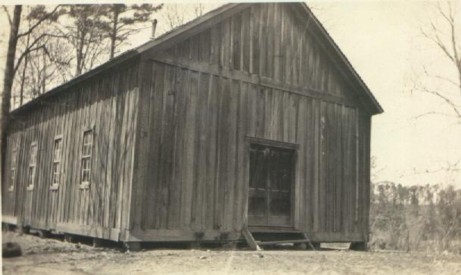

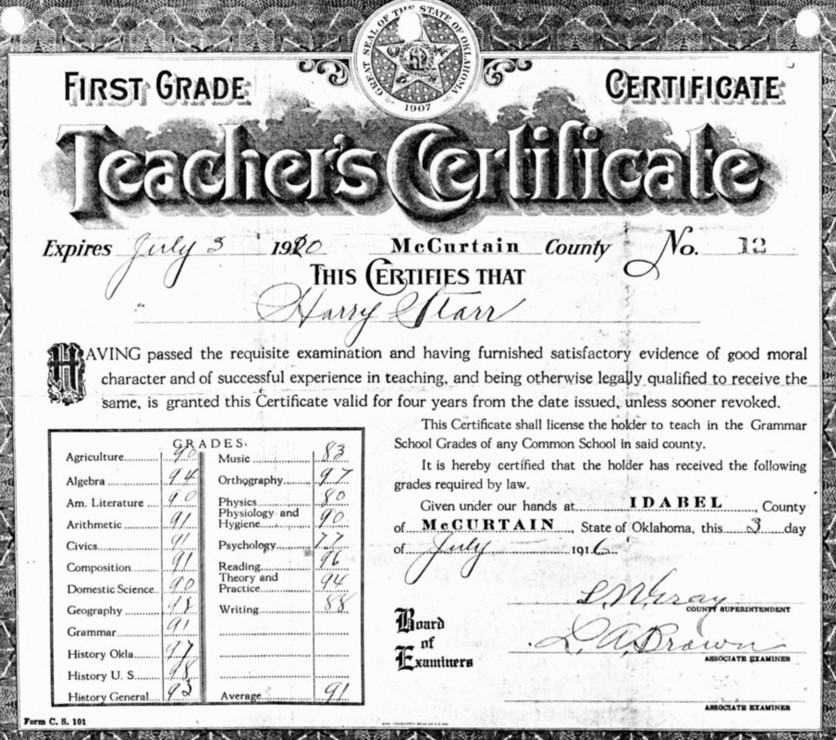

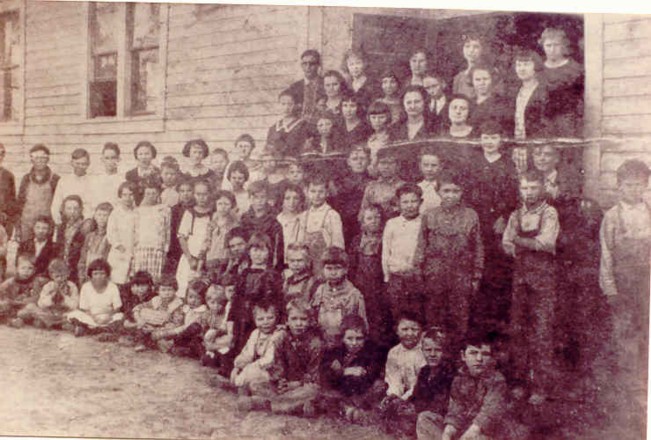

GLADYS: This area was heavily timbered, and although there were

many logging camps, there were no schools. My father had 3 school age

children and it disturbed him that there were no learning facilities

for them and the other children in the camps. So he decided to

take a giant step and open a school. He had had two years of college

training and he felt capable of teaching the basic three

“Rs” - reading, ‘riting and

‘rithmatic. [He received a temporary teacher's certificate in

1911.] Word was passed and school opened in the

one church that served the area. The building has been maintained

and still stands [1986] near Watson, Oklahoma. Imagine his amazement

when 90 children showed up for school! They ranged in age from 6

to 16 and only one of the entire group had had any previous schooling.

The 15 year old, Lee Blake, was at the 5th grade level. He became my

father’s assistant and school was in session for two hours each

day. Harry received a [regular] teacher’s certificate several

years later

and taught in a settlement known as Nuna Chito, an Indian name for

“Big Hill.”

(In 1911 Harry was one of five trustees of the Sulphur Springs

Methodist Episcopal Church, South, located at Watson, Oklahoma.

On March 1, L. L. Nichols and Ida Nichols sold a plot of

land for $1 to be used for the church. The other trustees

were: E. E. Collins, J. H. Baucum, Josiah Helton and J. H.

Smithton.) The church is pictured below.

DAVID: Some of his favorite stories are

about the schools in

southeastern OK. On the first day, he found himself the teacher with a

room full of one hundred children, seventy who could not speak a word

of English. His knowledge of the Indian language was sometimes

not enough, but this did not stump him. He just used

a little Spanish

that he learned while in Cuba.

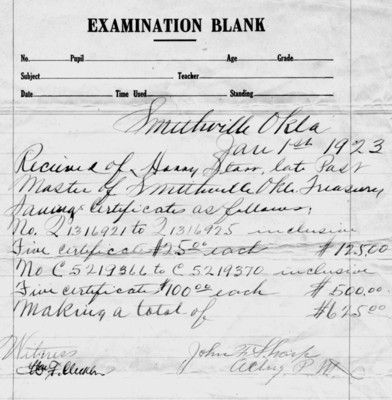

JACK: Pauline and Harry lived in numerous communities. They moved

to Watson, Oklahoma from Cove, Arkansas and farmed there. A

school was formed, but it needed a teacher. Harry was the only one

around qualified to teach, so he traveled to Idabel, the county seat

for McCurtain County, to take a seminar to help him qualify.

He started

his teaching career at Watson. In his first school there was 105

students. Sixty-five of them were Choctaw Indians and couldn’t

speak English. Harry had learned the Choctaw language so was able

to converse with them. The first textbooks were mail-order catalogs.

He

continued farming as well as teaching. He raised the best cotton he had

ever raised in 1913. The price, however, dropped to five cents a

pound so he left it in the field and vowed he would never plant cotton

again.

Harry, at left, in Idabel. Woman may be Pauline, but picture only identified Harry.

That was in the early days of Oklahoma right after statehood. I

didn’t start to school until about 1920 whereas Papa taught

school shortly after statehood. I don’t know just what year it

was, but I do know he was teaching at Watson about the time I was born,

1913.There were a lot of whites in there then, but of course, there

were a lot of Indians because it had been the Choctaw Indian Nation.

This is the school where they used the catalogs for books at first.

That was timber country then and there were lots of saw mills,

independent little sawmills around, which hired quite a few people. Of

course, those people had lots of children. And they moved those saw

mills a lot and the people came and went.

Catalogs accumulated in the Post Office because people didn’t

pick them up and they weren’t returned in those days. They

accumulated a whole stack of Montgomery Ward and Sears Roebuck catalogs

in a back corner. They took the catalogs to the school and used them

until they could get some books. I understand they used those catalogs

for most of that first year. It was a pretty good idea because the

reading in the catalog was related to the picture.

Two rental houses in which Harry, Pauline and the children lived before the move to Smithville.

When they wanted a teacher they didn’t have anyone to teach. My

Dad became the teacher as he was about as qualified as anyone could be.

He had, I guess you might say, finished high school. I’m not sure

he had, but he went to school in Calhoun to become a mathematician.

They got him to go down to Idabel to take a seminar like thing and he

got a teaching certificate. When he came back he became the teacher. He

taught for a number of years after that. After we moved to

Smithville, he taught school at Octavia and had to walk about five

miles to the school. I remember one morning there was snow on the

ground and he got up and wrapped his feet with tow sacks and tied them

on with strings so his feet wouldn’t freeze while he walked the

five miles to school.

The Smithville Years

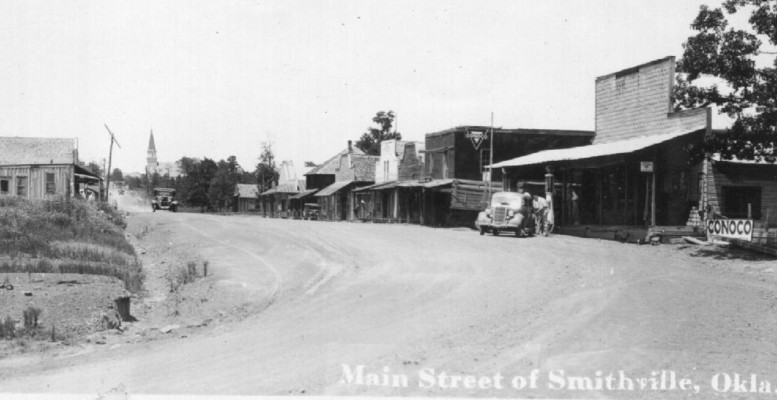

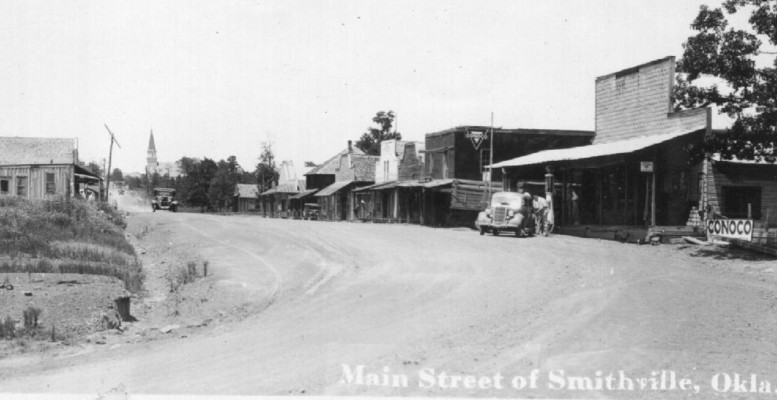

ALICE: We moved to Smithville in 1916. At the time it had four

general stores, a post office and a bank was there for a while.

When we moved there, Papa was the postmaster. And then he taught

school. He quit the sawmill business. He started teaching and did a

little farming. We always had a crop ... had a cow for our own

milk and butter and chickens. JS: They had a very

good garden. Must have had a half-acre in that garden.

ALICE: More I’d guess.

The Smithville house.

DAVID: They purchased the large nine room white house overlooking

the valley [near Smithville] for one thousand dollars. Harry was very

proud of his church, a small wood building that was donated to the town

by Folsom Training School. Countless times as we topped the last

hill before coming into town, he pointed with pride to the

glistening tall steeple and said “There is one of the most

beautiful and inspirational sights you will ever see.”

Two views of the structure that served Folsom Training Institute as a

chapel, and later as Smithville's Methodist church. It no longer stands.

JACK: When I was a small child Smithville was quite a little

village. There were stores for over a block on each side of the road

and some were pretty good sized stores. The Lebold Lumber Company was

operating there then. They had a sidewalk boardwalk all the way

up. It was quite a town. I can remember one time when I was

a little bitty kid we were downtown. Some guy had gotten drunk, got on

a horse and got up on that boardwalk. He was riding the horse up and

down on that boardwalk. It made a terrible noise and everybody was

excited. We didn’t have any saloons in the town, but there

was plenty of whiskey around. Back in the 20s that was one of the main

whiskey making areas of the state. The area around Hochatown became

quite famous. They called it Hochatown Hooch. It was back in the

mountains to the south between Smithville and Broken Bow. In fact,

Hochatown was covered up by the Broken Bow Reservoir. They had to

move the town, but I don’t think there was much of a town to

move. There were lots of canyons and rough country. They made

lots of whiskey in there and trucked it out across the state during

prohibition days. That was a big deal.

Gladys at about age

five.

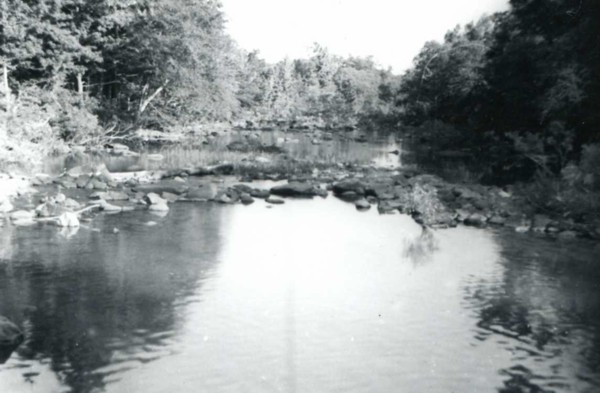

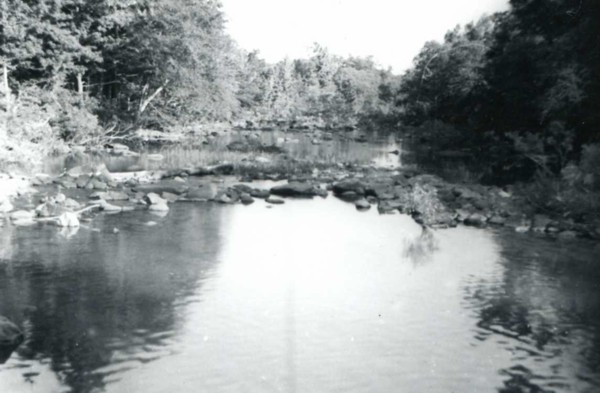

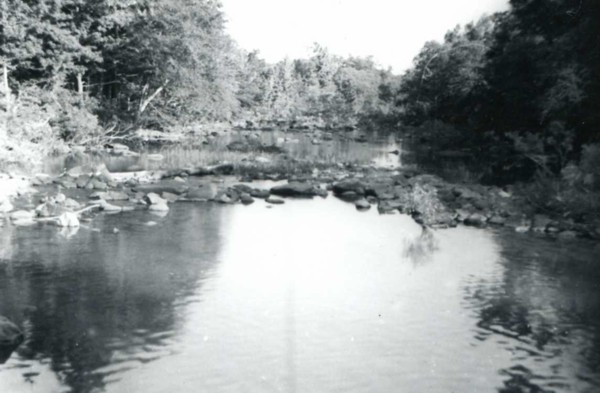

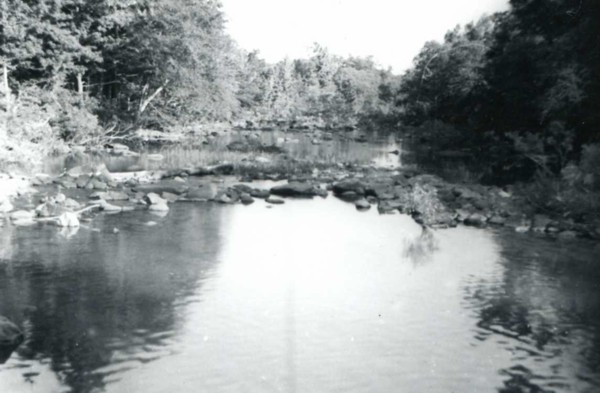

Mountain Fork river near Smithville.

JS: We enjoyed Smithville when we moved there. I had never lived

in a country where there was pine trees and real running water like

that. I thought that was one of the most ideal places in the world when

I moved out there. I loved to flyfish and if I fished more than 30

yards up the stream and didn’t catch enough fish, the fish were

not biting.

This picture of Smithville appears to have been taken about 1937.

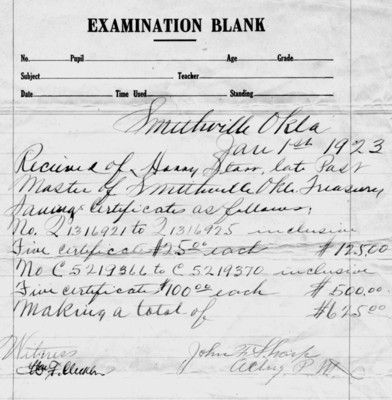

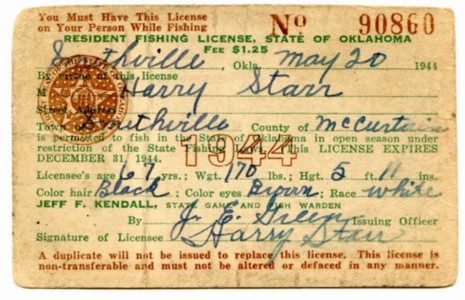

JACK: Democrat Woodrow Wilson was President when the family moved

to Smithville. Harry, a Democrat, was appointed Postmaster in 1916. He

ran a store in conjunction with the post office. With the election

of a Republican President in 1920, Harry lost his job as

postmaster. He then worked as an estimator and buyer of timber

for the Cove Lumber Company. In later years he did the same work

for the Three States Lumber Company. In 1929 he began working for

himself, surveying, estimating and purchasing timber. Harry loved

the outdoors and had a special love for trees.

JACK: Democrat Woodrow Wilson was President when the family moved

to Smithville. Harry, a Democrat, was appointed Postmaster in 1916. He

ran a store in conjunction with the post office. With the election

of a Republican President in 1920, Harry lost his job as

postmaster. He then worked as an estimator and buyer of timber

for the Cove Lumber Company. In later years he did the same work

for the Three States Lumber Company. In 1929 he began working for

himself, surveying, estimating and purchasing timber. Harry loved

the outdoors and had a special love for trees.

HARRY: The funniest thing that ever happened to me. After working

for two hours on the books of the Post Master, a friend of mine

suggested that we take a snort. I readily

acquiesced. After we sampled the moonshine, we took a real

good drink. After going back to work my friend discovered that

his eyesight was not normal. I also found that my vision was not clear.

ALICE: Papa first worked for Blake Barkley. He’s the one

who wrote to Papa and told him to come, that he’d have a job when

he got there and he worked for him. Barkley sold out to

Dierks. Dierks first went to Arkansas then to Broken Bow.

JACK: My Dad worked for the Cove Lumber Company during the 20s. I

believe it was 1928 that the Cove Company sold out to Dierks Lumber

Company. They did that just before the depression. My Dad often said

that was the smartest move the Barton boys or Blake Barton who owned

the Cove Lumber Company, made. He sold out just before the depression.

He got his money from Dierks, went out west to Oregon which was new

country then, bought out there and made a lot of money later.

It was around 1928 before Papa had to work on his own. We made trips to

the courthouse in Idabel to handle some of the business transactions.

We hardly ever went to Mena, or anywhere, while I was growing up.

JERRY: Going to Idabel was an all day trip. JACK:

Yeah. We’d get up real early in the morning. Papa had a Star car

... we’d get in that car, an old touring car was about the only

kind of cars there were in those days. All with curtains on the

sides. They didn’t have any glass. The road from

Broken Bow to Idabel was a pretty good gravel road. In this day and

time it wouldn’t be called a very good road, but in those days,

it was considered a good road. From Broken Bow to Bethel was a

so-called highway. It had been graveled, but it wasn’t kept up

too good. It was passable; I mean you could get over it.

From Bethel to Smithville was another 18 miles. It wasn’t even a

graded road. Wagons and cars had made ruts forming a sort of trail

which you’d follow. There were a lot of places where you had to

drive real slow because it had washed out, had high centers and things,

or mud holes where you’d get stuck if you didn’t watch out.

And sometimes you would get stuck and would have to fool around and get

yourself out by getting some poles or something to put down so you

could get out of the mud hole.

We’d get up real early in the morning and start out about

daylight and we’d get back way in the night usually. All

we’d do is go down there; however, it was 55 miles down there and

55 miles back. In those days, 110 miles was quite a trip. That was a

long, lonesome road. You hardly ever met anybody on that trip,

especially after you got back past Broken Bow a ways. You pretty well

got out of civilization from there and I don’t remember ever

passing anybody. People weren’t going that fast. You went

over Carter Mountain about halfway between Broken Bow and Bethel. It

had a hairpin bend. You went up this canyon a long ways and then you

cut right back over yourself to go back up the mountain. Finally you

topped out the mountain over there and went down a long ridge going

down towards Broken Bow. Right now that’s in the area of the

Broken Bow Reservoir.

HARRY: (Letter dated March 27, 1925 in reply to his Uncle J. W.

Starr in Atlanta who was then working on a family history.)

“...There is another little item that I will call your attention

to with a little pride. Alice, William, Harry and Helen are members of

the M. E. Church South. You will notice in the Church papers that the

Church has an institution here called Fulsom Training School. I am

educating my children in it. William graduates this year, Alice, next

year and Helen the next. Harry is up at Bristow working for the Okla.

Pipe Line Co. He joined the Church this year. He got angry with the

faculty here and quit school. He is doing well and is well thought of

every where. ... I am working at the same job, timber buyer for

the Cove Lumber Co. I have not heard from the last letter that I wrote

you in regard to timber. We had a big deal last fall just west of us.

The Dierks people paid $224,000.00 for 24,000 acres. Timber is higher

here than in Ga. I hope to have a fine business this year and am

making a good start.”

JS: I worked with your Granddad in the woods when he was cruising

[surveying and estimating] timber for Shaw. Then he switched over to

Dierks. A lot of times he cruised the same pieces of timber. At first

he cruised for Shaw and then Dierks would buy it and he’d have to

go over the same thing. Well, he already knew what was there.

I've seen trees too close together and that big around you

couldn’t drive a car between them in the thicket, I mean,

millions and millions of board feet. I had a big time working with him.

He'd tell me about things that had happened.

JS: I worked with your Granddad in the woods when he was cruising

[surveying and estimating] timber for Shaw. Then he switched over to

Dierks. A lot of times he cruised the same pieces of timber. At first

he cruised for Shaw and then Dierks would buy it and he’d have to

go over the same thing. Well, he already knew what was there.

I've seen trees too close together and that big around you

couldn’t drive a car between them in the thicket, I mean,

millions and millions of board feet. I had a big time working with him.

He'd tell me about things that had happened.

He had a great big old compass, one that he got from the government

I

guess. He knew where every section line corner was at that end of

the county and he knew where everyone of them was, so far as I know. He

knew where the forty was and where the section line corner and

we’d start there. In those days if you looked real carefully you

could see where the old blaze mark the government surveyor had made on

the side of the tree – all grown over, but you could see them.

He’d say: “Now Jack, you take this corner –

keep to the section line to the corner plate and you follow on down to

the next corner or forty acres, and I’ll get on the inside about

25 to 30 yards and we’ll go around this forty.” And

when we got back, he had a record of about not more than five percent

error in estimating the amount of board feet on that place. I

don’t know what kind of formula he

used.

Harry's compass >>

I’ve told this story to Alice several times. We’d been out

all week – he camped out at night and we did our own cooking and

everything ... we’d go out Monday and be back on Friday. I

noticed he’d usually pull off a piece of something or other, a

pine or some little twig and chew on that twig. One day I noticed

him a talking to himself and a talking to himself. I said:

“Starr, there’s something intriguing me.” And

he said “What’s that?” I said:

“What in the world are you talking to yourself about so

much?” And he says: “By gum, I like to hear a

smart man talk.”

JACK: When Papa was working in the woods he was gone most of the day

and a lot of time, he didn’t have much of a dinner. Sometimes,

when I worked with him, we’d carry our dinner -- a few crackers

and a can of potted meat or pork-n-beans to eat at noon. We’d

just drink out of the creek for our water. There was always a

creek or stream of clear water nearby. I guess it was alright, because

it never hurt us. The streams in the mountains run through shoals

and rocks which I guess purifies the water if it is polluted.

In 1933 we were hunting timber and the next day after we were in there,

some deer hunters with some dogs found a guy dead in a thicket in

there. I don’t know how close we walked to him, but we walked all

over it. In estimating timber you have to see all the trees. I was

running the lines and Papa was working with me. I probably didn’t

get very close to him, but Papa might have gotten close. Of course, he

was looking at trees and not at something on the ground, so he might

have been pretty close and still not seen him. Anyhow, the man had been

there quite a while.

HARRY: (Letter to Veterans Bureau May 15th 1933): “I

served in this company until July 1898 and was found upon medical

examination to have become unable to serve farther in the infantry, and

for this reason, was transferred to the hospital corps. The above

happened at Miami, Florida. The disability occurred on account of

excessive drilling and was in line of duty. The disability was the same

as I now have and am drawing a pension for ... I wish to farther state

that at the time I was discharged from the service .... I was not

examined and no effort was made to ascertain my physical condition. ...

I farther wish to state that I am dependant upon this money to sustain

a wife and family of three children. I have no job and am unable to

perform a hard day’s labor.”

Childhood Memories

1931: L to R, Gladys, Jack, Helen, Harry, Willliam, Alice,

Seated: Harry, Ione, Pauline

JACK: Each of us kids was assigned a job. Mine was to get in the wood

and get up and build a fire in the morning. And on the days we washed,

I drew water out of the well, filled the wash pot and built a fire

around it. And then I drew water to fill the tubs for

washing. In the winter the house was cold, of course.

I slept upstairs and by the time I got down to where the stove was, I

was already cold. The first thing I did was to build a fire in the

heater in the living room. I’d put some paper in there and then

I’d put in some kindling. We’d chop up pine which makes a

kind of kindling that ignites pretty well. Pine is usually full of

pitch and it’ll burn almost like kerosene. I’d

then put a pine knot on the top of it and some more wood. Then

I’d pour a little kerosene in the bowels of the stove and throw a

match in there. It’d take off with a sound like a freight train,

and sometimes it’d get red hot clear up past the elbow.

It’s a wonder I didn’t burn the house down. But anyway,

you’d get warm in a hurry.

I’d warm myself, then go into the kitchen where the cookstove

was. Building a fire in the cook stove was a slower process. Too much

pine wood or fast burning wood causes poor cooking conditions. If you

got it too hot, then it’d cool off. We’d have split [slower

burning] wood for the cook stove. By the time I got it started,

the girls would be up. Helen was the one who cooked the breakfast then.

She’d come down and make biscuits, cook the bacon, make the gravy

and fry the eggs and stuff. That was the way it went when I was growing

up for over a period of several years. We had biscuits every

morning I guess. I don’t ever remember us not having hot biscuits

and butter. We had a cow we milked that furnished us with all the

butter and milk we wanted. I guess we had what you would call

buttermilk biscuits. Helen would usually make those biscuits and

she’d mix everything in but the liquid the night before. Like me

building the fire, she had it down to a science and she could make

those biscuits pretty fast. We always had a big breakfast.

I think that was due to my Dad. That was one of our main meals.

And we had things for breakfast a lot of people don’t have today,

like macaroni and cheese. That was one of our favorites and we liked it

for breakfast. Another thing we had was brains and eggs.

Every time we butchered, which we did occasionally, the first thing

we’d have was fresh brains and eggs for breakfast the next

morning.

JERRY: Dad says one of his chores was to get up early and get the

fire going on the stove. ALICE: That’s right.

The boys did that and the girls got up and cooked

breakfast. We had sausage and steak and ham and scrambled

eggs and hot biscuits and usually preserves and jelly.

Jerry: Where did the macaroni and cheese come in? ALICE: Sometimes

we’d have that too. Because when we’d have it and everybody

wasn’t up, Papa’d say “Come alive, macaroni and

cheese.” We all liked it and Mama could make it so

good. I’ve never eaten it anywhere that made it like Mama

did.

L to R: Ione, Gladys and Jack

Gladys

GLADYS: Breakfast at our house was a major meal and it was

usually prepared by the oldest girl at home. My father always built the

fire in the wood stove and put the kettle on. I was 12 or 13 when I

became chief breakfast chef. My two older sisters had gone away to

college and it was now my turn – but one I had not really longed

for. On winter days the cook stove had not heated the room to the

point of coziness and many times I would wait for the second or third

call before rising. Usually I set the table at night. The plates were

placed at the back of the stove to warm as the food was cooked. Besides

biscuits, there was oatmeal or cream of wheat, bacon or sausage, eggs

and of course, jelly and home made butter and coffee. After the

meal, there was clearing the table and doing the dishes. We had two

dishpans for this chore – one for washing and one for rinsing. I

washed and Ione dried. When this was done, the floor was swept and

mopped and my mother took over for preparation of the noon meal –

another hearty affair. Supper was usually leftovers from noon.

In the summer we always had watermelon in the afternoon, but always by

4 p.m. Partaking of the juicy melon later might induce

bed-wetting – the bane of my mother’s life. Each of

us made our own bed and, of course, dishes had to be done after each

meal. Two other chores stand out vividly in my memory. Sometime during

the day it was my task to clean and fill the kerosene lamps – a

job I loathed. We had eight lamps and the chimneys had to be washed and

wiped, the bowls filled with the oil, and the wicks trimmed. The

inventor of the incandescent bulb will always be, to me, one of the

heroes of all time. I always emerged from this chore reeking of

the smell of kerosene. The other distasteful task was emptying

the chamber pots – a job I assumed at about age 9. There were

three – one for Jack, one for my parents, and the one shared by

all the girls. After emptying them, they had to be scalded and

set in a sunny place to air until bedtime when they were brought in

again. Nocturnal noises I so well remember are the ringing of a cowbell

in the lane, the screech of an owl in the grove and the clang of the

lid on the chamber pot.

JACK: Life in summer sort of revolved around water. We

didn’t have running water at home; we had to draw it out of

wells. We went to the creek to take our baths. When I was a small

boy, we went swimming about everyday in the summer and we learned to

swim. We had a hole of water down on Rock Creek which was about a

quarter of a mile from our house. We’d go down there about every

day and swim and play. There was a big tree down there. The roots had

washed out from under it and it fell into the creek parallel to the

bank except it was in the water. The water was fairly deep there, about

5 or 6 feet. We’d got us a board and worked it around somehow

until we had a diving board there like the big city people had.

The Mountain Fork river was farther from the house, but afforded more

space to swim.

JERRY: A lady at work was

remembering the hand dug well of her

childhood; she mentioned frogs. JACK: In the

early days, before we had a wood curb on the well, it was impossible to

keep frogs out. It’s a kind of a wood box around the well.

You’d get some frogs in there in spite of an anything you’d

do, especially in the dry periods of the summer when there wasn’t

any water anywhere else. You could see them down there, swimming

around. You could usually get them out by just letting the bucket down

and holding it over near the frog. It’d go into the bucket and

you could pull it out. But about once a year we’d clean out

the well because there was always dirt and stuff that would fall off

the side of the dug well. It was my job to go down in there. I’d

sit on the bucket and they’d let me down into the well which was

about 30 feet deep.

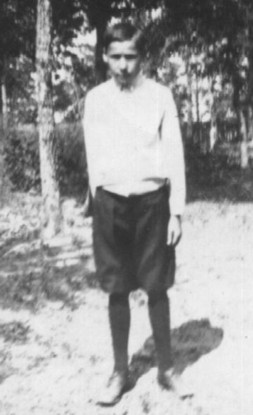

Jack, ca. 1926 >>>

We’d first draw all the water out we

could. We did this in the summer when the water level was pretty low

anyway. There was always water in there, but sometimes it would

be pretty slow in coming in. There was a water vein down there in the

rocks. We’d save some of the water that we drew out.

I’d take some implement and a broom with me to clean the dirt out

of the crevices in the rocks. The rocks were creviced from the blasts

of dynamite used when digging the well. I’d clean them the best I

could. They’d send down buckets of the saved water and I’d

throw it on the crevices and scrub and slosh it around, rinse it out

and when I got through, it was really clean. Then I’d get on my

bucket and they’d pull me back out. Afterwards, the water

would come back in. It does sound unsanitary, but that’s the kind

of thing you have to put up with when you have a dug well.

Grandchildren Gerald and Kathryn Jean Starr watch as Harry demonstrates

building a fire under the old wash pot. Note old outhouse in back. ca.

1951

GLADYS: Monday was washday if it was not raining. Jack drew the

water from the well and filled the tubs and wash pot. Then he

built a fire around the pot. By 7 a.m. Mrs. Mowdy arrived. The clothes

were scrubbed on a rub-board, then put into the pot of boiling sudsy

water. After a period of boiling, they were lifted out with the

punching stick and put into the first rinse. There they were swished

and wrung by hand and then placed into the second rinse. The bluing

rinse followed. Starch was cooked inside on the cook stove and

items that required starching went through this procedure before being

hung on the lines to dry. Shirt collars and fronts took heavy starch

and pillow cases, napkins, dresses, khaki pants, and dressier scarves

took a lighter starch. Mrs. Mowdy had noon meal with us and

finished afterward if she had not done so before. For her full morning

of labor, Mrs. Mowdy was paid $1 and her lunch. The trip from her house

to ours was a two mile walk. In the late afternoon, the clothes were

brought in and sprinkled down for Tuesday’s ironing.

Everything was ironed. The kitchen stove was heated to a frenzy

and the sadirons were placed on top to heat. Ironing was an all day

chore but the clothes always smelled fresh, soft and clean.

JACK: The first school I attended was a school at Smithville for eight

grades. It had three classrooms and a small room used for an eating

room with a place for a table and the dinner buckets. They also kept

wood in there. The first and second grades were in one room; then

another room had the third, fourth and fifth graders; with the sixth,

seventh and eighth grades in the largest room. The principal usually

taught in there. I don’t know how many students we had, but I

imagine there was 100 or so altogether. They didn’t have

kindergarten in those days. There were several Indians that went to

school there. A lot of the Indian kids, even in those days, went to

Indian schools, but there were several families that sent their

children to Smithville Public School.

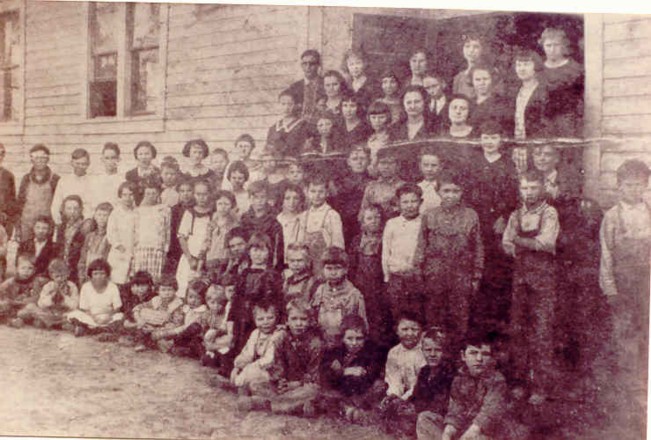

Gladys and Jack at the Smithville school. They are at the very

center; Jack is wearing overalls.

GLADYS: In 1929 I was thirteen and started to high school. It was also

the year the depression started. I do not recall that there was any

great change in our lifestyle. There had never been a lot of money at

our house. My parents owned their home. I’m sure they had many

worrisome hours about providing for the family, but we always ate and

had ample clothing. It was not until 1934 that I realized

the full meaning of hard times. I was 18, graduated from high school

and married two days after graduation to a boy in the local CCC camp.

Between us we had $12.50 and the license and minister’s fee cost

us five of that. He had only one month left in his camp time and

when that was done, we left by train for his home, Chelsea, Oklahoma.

His mother was a widow and he had two younger sisters at home. For a

few months we lived with them getting an odd job to earn money now and

then. After a year my husband became ill with tuberculosis. The doctor

told us it was worsened from breathing flour dust in the mill and that

he must find outside work to do. So we moved back to Smithville and my

folks. My father sometimes needed a man to go with him on his timber

estimates. I stayed with my mother while they were out on these trips

which sometimes took two or three days. That year we made a huge garden

and I canned over 500 jars of food to help stock the larder.

JACK: Pauline enjoyed tools and ordered the ones that appealed to

her. Sometimes the family worried she might harm herself using

them, and hid them from her. Pauline had a fear of lightening and

didn’t like trees to grow close to the house. One time she

decided to saw down a small tree that she considered would grow too

close to the house. She had sawed at least a third of the way

through the trunk before it was discovered. Reprimanded many

times by her adult children “to not overdo” she enjoyed the

smug satisfaction of her efforts. Pauline’s failing

health forced them to move to Mena, Arkansas in 1951 where medical help

was more available. ALICE: We moved from Smithville in 1953.

The modest but comfortable residence of Harry and Pauline on 7th Street

in Mena, Arkansas

Memories

DAVID: [Grandpa] made his way into my heart when he tagged the name

“Little Prime Minister” on me. He [another time] explained:

“After all, not everyone has been named after a

King.” [The first reference appears to be to David Lloyd

George, a British statesman; the second presumably to King David of the

Bible.] Then he got on all fours and crawled around the room

with me on his back. I was overjoyed. He was about 65 years of

age when I first remember him; but he was, and still is, tall and

straight, appearing to be much younger than his years. Even today, he

can quote verse from many famous works. He was a good scholar but

perhaps enjoyed mathematics, history and English the best of all

subjects. It was easy for him to make friends for he never knew a

stranger. He has a nervous habit of walking back and forth across the

room, head bowed and hands clasped behind his back. In retirement he

spends hours playing solitaire, wearing out decks of cards. He

follows all sports, but baseball is his favorite. He can recite

statistics of all the major ball teams. He has attended several World

Series games and can remember nearly every

play.

JERRY: I remember my grandfather as being very quiet, pretty withdrawn.

Was he? ALICE: He was reserved, but he could talk if you

asked him to. JS: Yeah, he could talk ... Usually he didn’t

pop off. What he had to say was really something to say.

JERRY: My grandparents were well up in the years when I

became old enough to remember much about them. Grandpa was tall, slim

and stood straight despite his age. His complexion was dark and one

might have guessed him to have Indian blood. He spent a lot of time

sitting in a rocking chair, listening to baseball games, smoking

hand-rolled cigarettes, putting the butts into an old roasting pan

filled with sand. His fingertips were stained by nicotine.

Grandma was short and quite plump. Her complexion was fair. In

old age she developed a marked dowager’s stoop. Her health

was poor and ... she had limited mobility. ... He dressed simply,

but my mother recalled he used to buy Kuppenheimer suits. There was a

time bankers and lawyers wore Kuppenheimer. ... Until the

early 50’s he still drove, and he liked to get in his old Ford

and “go to town” which in Smithville meant a couple stores,

the post office and a few houses. ....

JEAN: I remember Smithville as a sleepy little wide spot in the

road with the occasional pig crossing the road. Over the years we

traveled there to be nibbled on by ticks and mosquitoes and sat in the

hot church during long services. I fondly remember: Uncle Harry

bouncing a ball off of his head and singing ‘Frog Went

A’Courtin’; sitting next to Grandpa at the dining table and

watching his chin touch his nose with utter fascination; hiding

the little rubber snake in Grandpa’s bed and the resulting

hullaballoo; brushing and braiding Grandma’s long hair that she

tied at the end with hair from her brush; standing beside Grandpa as he

listened to ballgames and played solitaire at his roll-top desk;

playing with Grandma’s buttons (collected from worn-out clothing

and collected in a metal can over the years – better than

diamonds to a little girl.) And then there was riding down the

steep hill in Grandpa’s old car.

Harry in his "hiking and fishing" garb

Celebrating Pauline's 80th birthday: L

to R: Helen, Pauline, Jack, Alice, Harry Jr., Milam Wade, Gladys

LKS: In addition to the recollections present above, mention should be

made of Harry's attempt to become a published author. About 1953 he

finished a novel, "Fear Nothing", about a young man who comes to the

Indian Territory in the late 1800s to board with Choctaw families and

teach school. The title refers to the Indians' religious faith and code

of honor. Harry felt close to the Choctaws, learned some of their

language, and utilized his observations of Indian culture in writing

the book. The protaganist's supposed memoir is in a romantic and

moralistic style, familiar to Victorian readers but quite out of date

in our time. Primarily, however, it is a sympathetic description of a

culture and way of life that has virtually disappeared. Reportedly

Harry sent it to a woman in Tulsa who was to prepare a

professionally-typed manuscript and see to its publication. That did

not happen--indeed, the family thought the woman took advantage of

him--but

the original manuscript, typed laboriously on Harry's ancient

typewriter, survives. Images of the title page and a couple of pages of

texts, marked up with Harry's handwritten corrections and changes, can

be seen here.

* * *

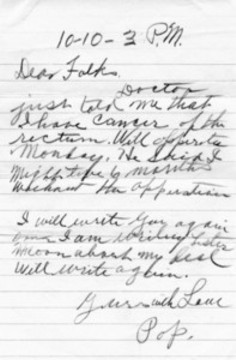

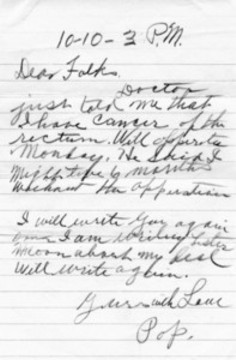

Harry died 21 December 1956 of colon cancer in the Veterans Hospital,

Little Rock, Arkansas.

Harry died 21 December 1956 of colon cancer in the Veterans Hospital,

Little Rock, Arkansas.

After spending a few years with her daughter,

Helen Wade, in Dallas, Pauline and daughter Alice Starr returned

to the Mena, Arkansas home. Pauline died there 29 January

1966.

Harry and Pauline are buried in the Starr plot at the Mena Cemetery

with four of their children and one son-in-law: William P., Helen Wade,

Alice Schisler and Gladys and Paul Campbell.

Harry and Pauline had eight children: Alice, William, Harry Jr., Estelle (died in infancy), Helen, Jack, Gladys and Ione.

Although both grew up in middle class Georgia households, the early

years for Harry and Pauline couldn’t have been more diverse if

one designed them to be. Harry, reared by a single father, grew up in a

small rural Georgia community south of Atlanta. His father was a

medical doctor, but they likely lived on the profits from the small

general merchandise store he operated on the side. Understandably,

between two careers, Dr. John had little time for his growing son.

Harry’s Aunt Mary (Griffin) Tucker and her husband Thomas

welcomed Harry into their home at all hours of the day and night.

Although both grew up in middle class Georgia households, the early

years for Harry and Pauline couldn’t have been more diverse if

one designed them to be. Harry, reared by a single father, grew up in a

small rural Georgia community south of Atlanta. His father was a

medical doctor, but they likely lived on the profits from the small

general merchandise store he operated on the side. Understandably,

between two careers, Dr. John had little time for his growing son.

Harry’s Aunt Mary (Griffin) Tucker and her husband Thomas

welcomed Harry into their home at all hours of the day and night. The bustling city of Calhoun was a far cry from little Sunnyside.

Located on the direct railroad route between Atlanta and Chattanooga,

it was competing successfully with other communities for new industries

along that corridor. Pauline’s father purchased the nearest

boarding house/hotel to the train depot, giving Pauline opportunity to

meet travelers from all over. The trains took members of the

Rankin family back to South Carolina for semi-regular visits with

relatives. Thus during her early years Pauline was exposed to a far

wider world than was Harry. Moreover, Pauline’s father was a

well-known and respected local and state politician and had diverse

business interests. Little happened that escaped discussion

around their dinner table.

The bustling city of Calhoun was a far cry from little Sunnyside.

Located on the direct railroad route between Atlanta and Chattanooga,

it was competing successfully with other communities for new industries

along that corridor. Pauline’s father purchased the nearest

boarding house/hotel to the train depot, giving Pauline opportunity to

meet travelers from all over. The trains took members of the

Rankin family back to South Carolina for semi-regular visits with

relatives. Thus during her early years Pauline was exposed to a far

wider world than was Harry. Moreover, Pauline’s father was a

well-known and respected local and state politician and had diverse

business interests. Little happened that escaped discussion

around their dinner table.  Pauline was one of seven children. All received the best

education their father

could afford. The girls were brought up to be

“southern ladies.” This encompassed the arts of playing

a musical instrument, singing, giving recitations and conversing

with gentlemen. There would be others to do the drudgery of house

cleaning and laundry.

Pauline was one of seven children. All received the best

education their father

could afford. The girls were brought up to be

“southern ladies.” This encompassed the arts of playing

a musical instrument, singing, giving recitations and conversing

with gentlemen. There would be others to do the drudgery of house

cleaning and laundry.

“I enlisted at Austin Texas

on May 4th, 1898 in Co K of the

2nd Texas Vol. Inf. We

“I enlisted at Austin Texas

on May 4th, 1898 in Co K of the

2nd Texas Vol. Inf. We  were moved from there to Mobile Alabama thence

to Miami Fla. There in the month of July I was transferred to the

Hospital Corps. We were moved to Jacksonville Fla. and thence to

Savannah Ga. Here I was detached with two others for service in

Hospital Corps with Signal Corps. In December 1898 we were taken to

Havana Cuba and remained there until about May 1st, 1899. Then I was

transferred at my own request to the Hospital Ship Missouri. [Note: The

Missouri (the subject of the painting at right), one of America's

earliest hospital vessels, saw heroic service even before the war with

Spain. For an interesting account, go to this

site. The Missouri's

dramatic rescue in 1889 (before it became an American vessel) of the singking Danmark's passengers is depicted

here.] After

making a trip to Newport News, we went to Brooklyn N.Y. for repairs and

on Oct 16, 1899 we started to Manila P. I. and landed there about Dec

1st 1899. We left Manila P.I. about Jan 1st, 1900, and arrived in

San Francisco Calif in Feb 1900 where I remained on Duty until I was

discharged on May 4th 1900. I was given an honorable discharge by Major

A. C. Gerrard.” [file #1,490,903 Veterans

Administration]

were moved from there to Mobile Alabama thence

to Miami Fla. There in the month of July I was transferred to the

Hospital Corps. We were moved to Jacksonville Fla. and thence to

Savannah Ga. Here I was detached with two others for service in

Hospital Corps with Signal Corps. In December 1898 we were taken to

Havana Cuba and remained there until about May 1st, 1899. Then I was

transferred at my own request to the Hospital Ship Missouri. [Note: The

Missouri (the subject of the painting at right), one of America's

earliest hospital vessels, saw heroic service even before the war with

Spain. For an interesting account, go to this

site. The Missouri's

dramatic rescue in 1889 (before it became an American vessel) of the singking Danmark's passengers is depicted

here.] After

making a trip to Newport News, we went to Brooklyn N.Y. for repairs and

on Oct 16, 1899 we started to Manila P. I. and landed there about Dec

1st 1899. We left Manila P.I. about Jan 1st, 1900, and arrived in

San Francisco Calif in Feb 1900 where I remained on Duty until I was

discharged on May 4th 1900. I was given an honorable discharge by Major

A. C. Gerrard.” [file #1,490,903 Veterans

Administration]

was amazed that Pauline did not know to

“break” the water by adding a little lye. Pauline was

even more amazed when the lady offered to do the laundry for her. This

gesture shocked her. She had never heard of white folks hiring out to

do laundry. But she was delighted and Pauline became the first woman in

the camp to hire a laundress. I heard Mom tell this story many

times.

was amazed that Pauline did not know to

“break” the water by adding a little lye. Pauline was

even more amazed when the lady offered to do the laundry for her. This

gesture shocked her. She had never heard of white folks hiring out to

do laundry. But she was delighted and Pauline became the first woman in

the camp to hire a laundress. I heard Mom tell this story many

times.

DAVID: Some of his favorite stories are

about the schools in

southeastern OK. On the first day, he found himself the teacher with a

room full of one hundred children, seventy who could not speak a word

of English. His knowledge of the Indian language was sometimes

not enough, but this did not stump him. He just used

DAVID: Some of his favorite stories are

about the schools in

southeastern OK. On the first day, he found himself the teacher with a

room full of one hundred children, seventy who could not speak a word

of English. His knowledge of the Indian language was sometimes

not enough, but this did not stump him. He just used

JACK: Democrat Woodrow Wilson was President when the family moved

to Smithville. Harry, a Democrat, was appointed Postmaster in 1916. He

ran a store in conjunction with the post office. With the election

of a Republican President in 1920, Harry lost his job as

postmaster. He then worked as an estimator and buyer of timber

for the Cove Lumber Company. In later years he did the same work

for the Three States Lumber Company. In 1929 he began working for

himself, surveying, estimating and purchasing timber. Harry loved

the outdoors and had a special love for trees.

JACK: Democrat Woodrow Wilson was President when the family moved

to Smithville. Harry, a Democrat, was appointed Postmaster in 1916. He

ran a store in conjunction with the post office. With the election

of a Republican President in 1920, Harry lost his job as

postmaster. He then worked as an estimator and buyer of timber

for the Cove Lumber Company. In later years he did the same work

for the Three States Lumber Company. In 1929 he began working for

himself, surveying, estimating and purchasing timber. Harry loved

the outdoors and had a special love for trees.

JERRY: A lady at work was

remembering the hand dug well of her

childhood; she mentioned frogs. JACK: In the

early days, before we had a wood curb on the well, it was impossible to

keep frogs out. It’s a kind of a wood box around the well.

You’d get some frogs in there in spite of an anything you’d

do, especially in the dry periods of the summer when there wasn’t

any water anywhere else. You could see them down there, swimming

around. You could usually get them out by just letting the bucket down

and holding it over near the frog. It’d go into the bucket and

you could pull it out. But about once a year we’d clean out

the well because there was always dirt and stuff that would fall off

the side of the dug well. It was my job to go down in there. I’d

sit on the bucket and they’d let me down into the well which was

about 30 feet deep.

JERRY: A lady at work was

remembering the hand dug well of her

childhood; she mentioned frogs. JACK: In the

early days, before we had a wood curb on the well, it was impossible to

keep frogs out. It’s a kind of a wood box around the well.

You’d get some frogs in there in spite of an anything you’d

do, especially in the dry periods of the summer when there wasn’t

any water anywhere else. You could see them down there, swimming

around. You could usually get them out by just letting the bucket down

and holding it over near the frog. It’d go into the bucket and

you could pull it out. But about once a year we’d clean out

the well because there was always dirt and stuff that would fall off

the side of the dug well. It was my job to go down in there. I’d

sit on the bucket and they’d let me down into the well which was

about 30 feet deep.

Harry died 21 December 1956 of colon cancer in the Veterans Hospital,

Little Rock, Arkansas.

Harry died 21 December 1956 of colon cancer in the Veterans Hospital,

Little Rock, Arkansas.