and

Jack Schisler

Copyright 2013 by Linda Sparks Starr

Jack and Alice in 1981

Alice Margaret Starr was delivered

by her grandfather, Dr. John P. Starr, the 9th day of September 1901 in

Sunnyside, Georgia. Not only was she the eldest child of Harry and

Pauline (Rankin) Starr, but she was the first grandchild on both the

Starr and Rankin sides of the family. Following southern tradition

engrained in Pauline, she was named for her grandmothers: Alice

(Griffin) Starr and Margaret (Ramsay) Rankin. Three more children

were born in quick succession: Bill and Harry (1902 and 1904

respectively) and Pauline Estelle in 1905. The next year her family

moved to the area around Cove, Arkansas, where Harry had found work in

the budding lumber industry.

Hard times came to the sawmill community not long after the family arrived. Her parents decided to sell-out and return to Georgia where family would take them in until Harry found work of some kind. It was decided Pauline and the children would go first and Harry would follow after he located a buyer for the stock and household items. Even though it was difficult for Pauline, separated from her husband, Alice always had fond memories of this return visit to Georgia. Harry wasn’t all that eager to return to Georgia and he managed to get by with only himself to feed. After a few months, Pauline realized she and the children would have to return to Oklahoma if they wanted to see Harry again. She asked her father for a loan of the ticket price back to Cove. Just before boarding the train, Alice’s grandpa Rankin gave her a small child’s tea cup with the words “Remember me” on the side. Since grown-ups are wont to say this, I’m sure at least one of her aunts said: “Alice, help your Mom look after the boys on the trip back.” Alice took those words and her role as eldest child seriously. Although her siblings tended to tune her out, the in-laws were known to occasionally mumble about her bossiness.

I say this with all fondness: Alice was the Miss Pittypat of the family. Although she gloried in her role of being “big sister,” the family joined in a loving conspiracy to protect her from learning ALL that went on in their worlds. For example: Alice was a tee-totaler with no compunction about expressing her view. Bottles of stronger-than-cola-liquids were moved to the back of bottom cabinets before she arrived. She had specific opinions about how children should behave – the behavior based on expectations of her childhood – and how grown-ups should respond when they didn’t. She wasn’t above stating her opinions in a voice loud enough to carry.

The southern heritage Alice clearly viewed through rose-colored glasses meant a great deal to her. She often spoke of those living in the war years as if they had only recently died. [For non-southern readers, that’s the war between the states.] Although she grew up far from her Georgia cousins, she and Helen attended many Rankin/Ramsay family reunions held near Toccoa, Georgia. Many of the older attendees’ parents and certainly their grandparents lived through those years. The highlight of these reunions was exchanging family stories in afternoon gatherings under shade trees. A niece once described her vision of her aunts Alice and Helen at such events: “Helen would sit with notebook and pencil in hand, writing furiously and occasionally asking for repeats of dates and names. Alice would just sit back and enjoy the stories.” Although the number of acres owned by her ancestors seem to grow with each of Alice’s tellings, we are lucky to have had both in the family. Much to the dismay of their sister Gladys, who was left with the task of clearing out their spaces, neither discarded anything relating to family, especially holiday cards.

In 1923 Alice registered for her first term of high school level coursework at Fulsom Training School, a Methodist Indian Mission school located near the Starr home in Smithville, Oklahoma. The school was on the north side of Smithville, just a few hundred yards down the hill from the Starr house. Although set up as a boarding school for Indians from all tribes, anyone could attend. Students either paid tuition and room and board outright or worked at the school in exchange for their education. Life-long friendships between many students and teachers were maintained by annual gatherings fondly known asThe Fulsom Reunion. Until the old Fulsom chapel was razed, the reunions were held on the grounds of the school. Saturday was devoted to conversation, splendid covered-dish meals and slicing up big, cold Black Diamond watermelons. Sunday morning there was a church service in the chapel and a business meeting for the alumni association. In the later years reunions were held in various locations in southeast Oklahoma.

Alice’s teachers included Mrs. Hubbell who taught all the English classes, home science and occasionally history. Additionally, she was wife of the school superintendent. Rev. Nisbett taught agriculture, Bible, civics and probably history. More importantly, he was also the minister of the Methodist Church affiliated with Fulsom Training School. Students were expected to support the little academic community by performing various jobs such as cooking meals, cleaning buildings and caring for animals that provided milk and meat. It’s easy to see how Fulsom developed into the largely self-contained community it eventually became.

Jack Schisler taught all the math and science courses. Several summer days he worked alongside Alice’s father, laying the chains as Harry measured off timberland and estimated the potential board feet of lumber in each section. Jack and his wife were just starting their family and the extra money was a godsend. Jack’s stories told about this time with Harry are priceless.

Alice graduated in 1926 with eight others. Blye and Floy Turrentine lived “down the road” from the Starrs and were life long friends, as was Lucille Johnson. Other names aren’t recognized, but no doubt she kept up with them too over the years. A short biography in the school newspaper provides insight into Alice in her early-twenties: “She entered Fulsom as a freshman, but did not continue with her high school work. She taught for a year then came back to Fulsom, determined to stay this time until she received a diploma. ... When she is through high school, Alice expects to teach and then to go on to college.“

Teaching before receiving a high school diploma seems incredible today. But Alice lived at a time when it was common for teachers in the younger grades to have only a little more training than the best educated student. Teachers would work until they’d save enough money to pay expenses for a few months. They’d then take a semester or two of coursework and return to the classroom to teach and save some more. This went on until the degree was in hand. Or as happened more often, the female teacher married and stopped teaching altogether. We must remember, Alice’s parents lived by the values under which they were raised and these were the values passed to their children. One distinct difference between then and now is it was then considered more important for men to be educated than women. Thus Alice’s younger brother, Bill, only took four years to receive his degree from the University of Tulsa. He worked for his room and board, but his parents helped him more with his tuition and books. On the other hand, it took Alice years to attain her degree. She surely received some financial help from her parents those first few years, but the larger part of their budget for secondary education went to the older son.

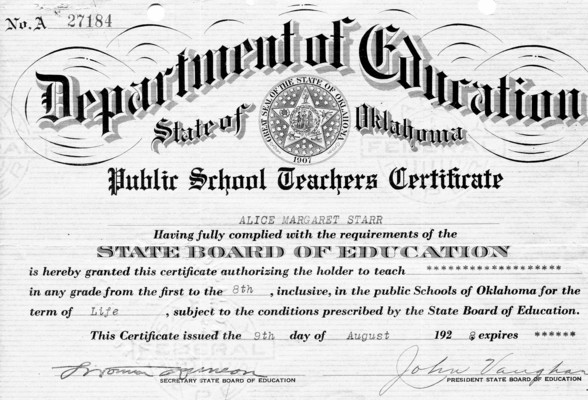

Alice received her official certificate August 1928 authorizing her to teach any grade, from first to eighth:

Two early schools she taught at were Stonewall and Haworth according to her sister. We assume this unidentified building and students are from this period. Gladys added that one was six miles away from their parent’s home, one way. Alice had no access to a personal car – we doubt she ever learned to drive – thus her mode of travel was by horseback. Luckily we have a picture to prove this, for her great-nieces and nephews (who met her when she was in her eighties) are unbelieving that “Aunt Alice once rode horseback or wore a swimsuit.”

Alice enrolled in coursework for the summer session 1931 at Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Oklahoma State University). According to her transcript, she had previously pursued a degree at the University of Tulsa and the George Peabody College for Teachers in Nashville, Tennessee. The work accepted was about two-thirds of what she needed for the final degree. However, the dates she attended these two institutions aren’t noted. It appears her original plan was to take three or four courses each summer until her degree was in hand. The Depression changed her plans as it did for many others. She attended classes in the summer of 1931 but not again until summer 1937.

Between 1933 and 1938 Alice taught nearer her parent’s home. Although she may have ridden horseback occasionally, this was an easy daily walk, much the same as when she attended Fulsom. She may have returned to Smithville to help her parents during the Depression years. Although they owned their home and raised most of the food needed, they still had children at Fulsom and probably a daughter was in business college. An occasional monetary contribution from Alice was welcome -- as was her help with household chores – but, living at home, allowed her to save more money towards her future college.

She took courses in Stillwater at Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State University) the summers of 1938 and 1939, then entered as a full time student fall and spring semesters 1941-1942. How proud and relieved she must have been to walk across the stage that June of 1942.

Alice’s last job in the southeastern part of Oklahoma was at Hugo for the 1942-1943 term. Her income tax form for that year shows income of $1070, all paid by the Board of Education. During the next twenty years Alice took short “how to” workshops and worked towards a masters degree at the University of Oklahoma. She attended at least one National Education Association convention held in Seattle 1964. This allowed her a chance to spend time with her sister and niece and nephews there. She remained active in the United Methodist Church throughout her life and took training workshops for Christian service.

By early 1950 Alice had moved to the Midwest City-Del City area. Both, now part of the larger Oklahoma City metro area, were then distinct and separate towns catering to families who worked at the adjacent Tinker Air Force Base. Alice settled into an apartment in 1956 where she lived until her move to Mena, Arkansas in 1965. Each year she purchased the Westside School classroom photo of herself and students along with several photos of the faculty. Unfortunately, most are not identified.

In 1965 Alice’s mother was living with Helen and Milam Wade in Dallas, Texas. The beautiful Wade home was built without thought to old-age disabilities. All three bedrooms, the bathtub and a shower were upstairs, while the only bath downstairs required going up and down a few steps. Dining areas and seating for visiting guests were all downstairs. Pauline’s arthritis had taken its toil by this date. Milam carried her up and down the stairs when needed; but most times, he and Helen sat with her in her room while she ate her meals from a tray. In Mena everything Pauline needed was on the ground floor. On her better days, she managed to sit outside in the garden. However, the real catalyst for change was Milam’s mother. Her health declined rapidly and he was the only sibling in a position to take charge of her situation.

At the end of the school term 1964-1965 Alice retired from teaching and moved to Mena, Arkansas to care for her mother. After Pauline’s death January 1966, Alice applied for an Arkansas Teaching Certificate. It lists her experience as: Alice Starr, age 64 with 35 years experience plus 29 hours extra credit in educational courses. She began teaching that fall at the elementary school “just down the hill” and worked there until her final retirement. However, in her heart she never did retire. When we were clearing out her Tulsa apartment at the time she moved into the nursing care center, we found boxes of lesson plans and bulletin board decorations in the back of one closet. These had been moved countless times.

Late summer 1976, without consulting family, including Gladys who actually owned the house in Mena, Alice sold it. She phoned her brother Jack, and without explanation: “I need to be out by xxx Can you and Jerry help?” She added, she’d rented an apartment (sight unseen) in the town where Jack lived. We arrived with U-Haul truck the day before she was to be out. She’d packed only a few things – linens, rocks and some rooted plant sprigs – all in plastic bags. Most everything else (especially including her collection of breakables) needed to be packed, but there were no empty boxes or packing materials in sight.

Alice had one more surprise for the family. On 6 June 1981 she phoned her siblings to tell them she and Jack Schisler had married that afternoon and Tulsa was her new home. Jack’s wife of many years had died the past year and, at their age, the two life-long friends saw no reason to wait once the decision was made. The Schisler children remembered Alice fondly as their first grade teacher and sometime baby-sitter from back when she taught in the Smithville School District. Also, they were part of the second generation who occasionally attended the Fulsom reunions and had kept up with Alice that way. Likewise, the Starr siblings all knew Jack as a life-long friend.

Arthritis was making life difficult for Jack, but Alice was able to bend from her waist or knees without a moment’s thought. She proudly claimed this was result of her doing stretching exercises every morning before she got out of bed. Thus she helped with his more difficult daily tasks and was there to pick up items or clean up spilled liquids. On the other hand, she was legally blind; but, his sight was 20/20 with glasses. They thoroughly enjoyed the afternoons when he read to her or both listened to Talking Books. Driving was not a problem for Jack, in fact he had a lead foot, and both loved to go places. He often drove them to visit her siblings and his daughter who lived nearby. They especially enjoyed going to restaurants. Their lively minds and interest in everything kept them young – and a joy to visit. They soon moved into an assisted living retirement home where they had eight wonderful years together.

Jack Schisler died of a heart attack 22 June 1989 and was buried beside his first wife in a Tulsa Cemetery. Alice remained in the same assisted living home, but moved into a one bedroom apartment. With her step-daughter’s help, she managed to continue much as she had before. She took advantage of outings offered to the residents and family and friends dropped by every chance they got. Sadly her step-daughter died a few years later. Alice turned to her nephew for help with bills, insurance and such things. A personal aide saw to her personal needs and provided companionship. Gladys was only a phone call away and Alice turned to her more and more. Alice loved to talk on the phone, but kept her conversations short for everyone but Gladys.

In early January 2000 her failing health forced her into the nearby nursing center. However, she had accomplished her last goal (or bucket list): living to see the new century come in. I don’t remember her saying she wanted to live to one hundred years. Alice died 7 April 2000 in Tulsa, Oklahoma and was buried in the Pinecrest Memorial Park, Mena, Arkansas alongside her parents, three siblings and a brother-in-law.

Hard times came to the sawmill community not long after the family arrived. Her parents decided to sell-out and return to Georgia where family would take them in until Harry found work of some kind. It was decided Pauline and the children would go first and Harry would follow after he located a buyer for the stock and household items. Even though it was difficult for Pauline, separated from her husband, Alice always had fond memories of this return visit to Georgia. Harry wasn’t all that eager to return to Georgia and he managed to get by with only himself to feed. After a few months, Pauline realized she and the children would have to return to Oklahoma if they wanted to see Harry again. She asked her father for a loan of the ticket price back to Cove. Just before boarding the train, Alice’s grandpa Rankin gave her a small child’s tea cup with the words “Remember me” on the side. Since grown-ups are wont to say this, I’m sure at least one of her aunts said: “Alice, help your Mom look after the boys on the trip back.” Alice took those words and her role as eldest child seriously. Although her siblings tended to tune her out, the in-laws were known to occasionally mumble about her bossiness.

| The gift from Grandpa Rankin |

Taken perhaps about 1918? |

Taken perhaps about 1950? |

I say this with all fondness: Alice was the Miss Pittypat of the family. Although she gloried in her role of being “big sister,” the family joined in a loving conspiracy to protect her from learning ALL that went on in their worlds. For example: Alice was a tee-totaler with no compunction about expressing her view. Bottles of stronger-than-cola-liquids were moved to the back of bottom cabinets before she arrived. She had specific opinions about how children should behave – the behavior based on expectations of her childhood – and how grown-ups should respond when they didn’t. She wasn’t above stating her opinions in a voice loud enough to carry.

The southern heritage Alice clearly viewed through rose-colored glasses meant a great deal to her. She often spoke of those living in the war years as if they had only recently died. [For non-southern readers, that’s the war between the states.] Although she grew up far from her Georgia cousins, she and Helen attended many Rankin/Ramsay family reunions held near Toccoa, Georgia. Many of the older attendees’ parents and certainly their grandparents lived through those years. The highlight of these reunions was exchanging family stories in afternoon gatherings under shade trees. A niece once described her vision of her aunts Alice and Helen at such events: “Helen would sit with notebook and pencil in hand, writing furiously and occasionally asking for repeats of dates and names. Alice would just sit back and enjoy the stories.” Although the number of acres owned by her ancestors seem to grow with each of Alice’s tellings, we are lucky to have had both in the family. Much to the dismay of their sister Gladys, who was left with the task of clearing out their spaces, neither discarded anything relating to family, especially holiday cards.

In 1923 Alice registered for her first term of high school level coursework at Fulsom Training School, a Methodist Indian Mission school located near the Starr home in Smithville, Oklahoma. The school was on the north side of Smithville, just a few hundred yards down the hill from the Starr house. Although set up as a boarding school for Indians from all tribes, anyone could attend. Students either paid tuition and room and board outright or worked at the school in exchange for their education. Life-long friendships between many students and teachers were maintained by annual gatherings fondly known asThe Fulsom Reunion. Until the old Fulsom chapel was razed, the reunions were held on the grounds of the school. Saturday was devoted to conversation, splendid covered-dish meals and slicing up big, cold Black Diamond watermelons. Sunday morning there was a church service in the chapel and a business meeting for the alumni association. In the later years reunions were held in various locations in southeast Oklahoma.

Alice’s teachers included Mrs. Hubbell who taught all the English classes, home science and occasionally history. Additionally, she was wife of the school superintendent. Rev. Nisbett taught agriculture, Bible, civics and probably history. More importantly, he was also the minister of the Methodist Church affiliated with Fulsom Training School. Students were expected to support the little academic community by performing various jobs such as cooking meals, cleaning buildings and caring for animals that provided milk and meat. It’s easy to see how Fulsom developed into the largely self-contained community it eventually became.

Jack Schisler taught all the math and science courses. Several summer days he worked alongside Alice’s father, laying the chains as Harry measured off timberland and estimated the potential board feet of lumber in each section. Jack and his wife were just starting their family and the extra money was a godsend. Jack’s stories told about this time with Harry are priceless.

| Alice's math teacher |

Most of Fulsom's faculty appear on this registration card. |

Jack on a Fulsom boardwalk |

Alice graduated in 1926 with eight others. Blye and Floy Turrentine lived “down the road” from the Starrs and were life long friends, as was Lucille Johnson. Other names aren’t recognized, but no doubt she kept up with them too over the years. A short biography in the school newspaper provides insight into Alice in her early-twenties: “She entered Fulsom as a freshman, but did not continue with her high school work. She taught for a year then came back to Fulsom, determined to stay this time until she received a diploma. ... When she is through high school, Alice expects to teach and then to go on to college.“

| Graduating from high school was a notable accomplishment in 1926. |

A class reunion--perhaps 25 years later. |

Teaching before receiving a high school diploma seems incredible today. But Alice lived at a time when it was common for teachers in the younger grades to have only a little more training than the best educated student. Teachers would work until they’d save enough money to pay expenses for a few months. They’d then take a semester or two of coursework and return to the classroom to teach and save some more. This went on until the degree was in hand. Or as happened more often, the female teacher married and stopped teaching altogether. We must remember, Alice’s parents lived by the values under which they were raised and these were the values passed to their children. One distinct difference between then and now is it was then considered more important for men to be educated than women. Thus Alice’s younger brother, Bill, only took four years to receive his degree from the University of Tulsa. He worked for his room and board, but his parents helped him more with his tuition and books. On the other hand, it took Alice years to attain her degree. She surely received some financial help from her parents those first few years, but the larger part of their budget for secondary education went to the older son.

Alice received her official certificate August 1928 authorizing her to teach any grade, from first to eighth:

Two early schools she taught at were Stonewall and Haworth according to her sister. We assume this unidentified building and students are from this period. Gladys added that one was six miles away from their parent’s home, one way. Alice had no access to a personal car – we doubt she ever learned to drive – thus her mode of travel was by horseback. Luckily we have a picture to prove this, for her great-nieces and nephews (who met her when she was in her eighties) are unbelieving that “Aunt Alice once rode horseback or wore a swimsuit.”

| Off to teach school. |

Bathing beauties. |

Alice enrolled in coursework for the summer session 1931 at Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Oklahoma State University). According to her transcript, she had previously pursued a degree at the University of Tulsa and the George Peabody College for Teachers in Nashville, Tennessee. The work accepted was about two-thirds of what she needed for the final degree. However, the dates she attended these two institutions aren’t noted. It appears her original plan was to take three or four courses each summer until her degree was in hand. The Depression changed her plans as it did for many others. She attended classes in the summer of 1931 but not again until summer 1937.

Between 1933 and 1938 Alice taught nearer her parent’s home. Although she may have ridden horseback occasionally, this was an easy daily walk, much the same as when she attended Fulsom. She may have returned to Smithville to help her parents during the Depression years. Although they owned their home and raised most of the food needed, they still had children at Fulsom and probably a daughter was in business college. An occasional monetary contribution from Alice was welcome -- as was her help with household chores – but, living at home, allowed her to save more money towards her future college.

| One of Aice's schools, but picture has no notation of place or when taken. |

Some of Alice's young students; again, year not known. |

She took courses in Stillwater at Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State University) the summers of 1938 and 1939, then entered as a full time student fall and spring semesters 1941-1942. How proud and relieved she must have been to walk across the stage that June of 1942.

| The proud graduate. |

She taught at Hugo, OK for the 1942-1943 term. |

Alice’s last job in the southeastern part of Oklahoma was at Hugo for the 1942-1943 term. Her income tax form for that year shows income of $1070, all paid by the Board of Education. During the next twenty years Alice took short “how to” workshops and worked towards a masters degree at the University of Oklahoma. She attended at least one National Education Association convention held in Seattle 1964. This allowed her a chance to spend time with her sister and niece and nephews there. She remained active in the United Methodist Church throughout her life and took training workshops for Christian service.

| Her 1946 teacher certificate. Note it is "for life". |

Her 1948-1949 class. The location is not known. |

By early 1950 Alice had moved to the Midwest City-Del City area. Both, now part of the larger Oklahoma City metro area, were then distinct and separate towns catering to families who worked at the adjacent Tinker Air Force Base. Alice settled into an apartment in 1956 where she lived until her move to Mena, Arkansas in 1965. Each year she purchased the Westside School classroom photo of herself and students along with several photos of the faculty. Unfortunately, most are not identified.

| Alice and one of her classes. Perhaps about 1960. |

In 1965 Alice’s mother was living with Helen and Milam Wade in Dallas, Texas. The beautiful Wade home was built without thought to old-age disabilities. All three bedrooms, the bathtub and a shower were upstairs, while the only bath downstairs required going up and down a few steps. Dining areas and seating for visiting guests were all downstairs. Pauline’s arthritis had taken its toil by this date. Milam carried her up and down the stairs when needed; but most times, he and Helen sat with her in her room while she ate her meals from a tray. In Mena everything Pauline needed was on the ground floor. On her better days, she managed to sit outside in the garden. However, the real catalyst for change was Milam’s mother. Her health declined rapidly and he was the only sibling in a position to take charge of her situation.

At the end of the school term 1964-1965 Alice retired from teaching and moved to Mena, Arkansas to care for her mother. After Pauline’s death January 1966, Alice applied for an Arkansas Teaching Certificate. It lists her experience as: Alice Starr, age 64 with 35 years experience plus 29 hours extra credit in educational courses. She began teaching that fall at the elementary school “just down the hill” and worked there until her final retirement. However, in her heart she never did retire. When we were clearing out her Tulsa apartment at the time she moved into the nursing care center, we found boxes of lesson plans and bulletin board decorations in the back of one closet. These had been moved countless times.

Late summer 1976, without consulting family, including Gladys who actually owned the house in Mena, Alice sold it. She phoned her brother Jack, and without explanation: “I need to be out by xxx Can you and Jerry help?” She added, she’d rented an apartment (sight unseen) in the town where Jack lived. We arrived with U-Haul truck the day before she was to be out. She’d packed only a few things – linens, rocks and some rooted plant sprigs – all in plastic bags. Most everything else (especially including her collection of breakables) needed to be packed, but there were no empty boxes or packing materials in sight.

Alice had one more surprise for the family. On 6 June 1981 she phoned her siblings to tell them she and Jack Schisler had married that afternoon and Tulsa was her new home. Jack’s wife of many years had died the past year and, at their age, the two life-long friends saw no reason to wait once the decision was made. The Schisler children remembered Alice fondly as their first grade teacher and sometime baby-sitter from back when she taught in the Smithville School District. Also, they were part of the second generation who occasionally attended the Fulsom reunions and had kept up with Alice that way. Likewise, the Starr siblings all knew Jack as a life-long friend.

Arthritis was making life difficult for Jack, but Alice was able to bend from her waist or knees without a moment’s thought. She proudly claimed this was result of her doing stretching exercises every morning before she got out of bed. Thus she helped with his more difficult daily tasks and was there to pick up items or clean up spilled liquids. On the other hand, she was legally blind; but, his sight was 20/20 with glasses. They thoroughly enjoyed the afternoons when he read to her or both listened to Talking Books. Driving was not a problem for Jack, in fact he had a lead foot, and both loved to go places. He often drove them to visit her siblings and his daughter who lived nearby. They especially enjoyed going to restaurants. Their lively minds and interest in everything kept them young – and a joy to visit. They soon moved into an assisted living retirement home where they had eight wonderful years together.

Jack Schisler died of a heart attack 22 June 1989 and was buried beside his first wife in a Tulsa Cemetery. Alice remained in the same assisted living home, but moved into a one bedroom apartment. With her step-daughter’s help, she managed to continue much as she had before. She took advantage of outings offered to the residents and family and friends dropped by every chance they got. Sadly her step-daughter died a few years later. Alice turned to her nephew for help with bills, insurance and such things. A personal aide saw to her personal needs and provided companionship. Gladys was only a phone call away and Alice turned to her more and more. Alice loved to talk on the phone, but kept her conversations short for everyone but Gladys.

| Alice in June, 1998; the last photo of her. |

In early January 2000 her failing health forced her into the nearby nursing center. However, she had accomplished her last goal (or bucket list): living to see the new century come in. I don’t remember her saying she wanted to live to one hundred years. Alice died 7 April 2000 in Tulsa, Oklahoma and was buried in the Pinecrest Memorial Park, Mena, Arkansas alongside her parents, three siblings and a brother-in-law.